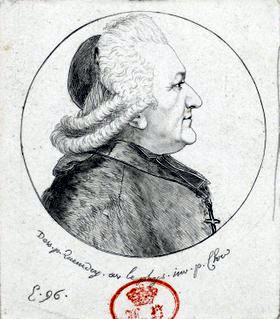

It is surprising to see the interest shown in Joseph de Galard de Saldebru, the last abbot of the abbey of Saint-Maurin, whose tenure was brief. He bore an illustrious name but his conduct was hardly noble, he was not in fact a holy man. Tenacious and reckless, once arrested he adopted a pitiful defence which denied both family and religion. It did not save him; a victim of the Revolution but not a martyr, he was executed on 17th February 1794 in Bordeaux. The man thus appears more mediocre than interesting. Why is he then the best known of the abbots of Saint-Maurin? No doubt because he was the last of them and because, ironically, he was swept away by national revolutionary turmoil. He had, however, also contributed to the initial local outbreak of the Revolution at Saint-Maurin through his attitude and actions.

His lineage and beginnings

Joseph de Galard de Saldebru was born in 1739 into an extremely well-connected family dating back to the 9th century, whose members held important military (1), religious or civil positions. The Galard de Saldebru are a branch of the Galard-Brassac family, which appeared at the beginning of the 17th century with Charles-Amaury (2), his great-great-grandfather, whose mother was a descendant of the Lustrac family that had provided abbots of Saint-Maurin. She was Anne de Geniès du Sap (4), who brought Saldebru into the family (3).

If the Galards of Saldebru could take pride in their prestigious cousins, they lived on the modest proceeds of their small estate of Salle de Bru or Saldebru sur Perville (photo of the chateau above) and the help of a brother, a priest. The latter provided Joseph de Galard with the initial means for his education and secured him a free place at the Petit Séminaire de Cahors. Galard became a priest and vicar of Montjoi and then vicar of Sainte-Croix. He had modest parishes, but the patronage of the eldest branch of the Galard-Terraube family, held in high regard at court, secured for him a canonry in the chapter of Notre-Dame in Paris, a benefice which he exchanged for the great chantry of Lectoure, when he became vicar-general there. He also became commendatory prior of the royal priory of N-D. du Fief Saurin (diocese of Angers) and of that of Louesne (diocese of Langres).

Marie-Joseph de Galard de Terraube, Joseph’s brother

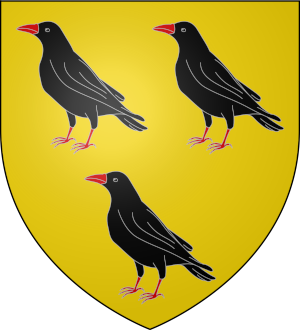

Coat of arms of the Galard de Terraube family

Commendatory abbot of Saint Maurin

It was then that he thought of the abbey of Saint-Maurin, on which his father had held a long-term lease (emphyteutic lease). The royal patronage of the Galard-Terraube family ensured that the incumbent, Joseph de Crémaud d’Entraigues, vicar-general of Bordeaux, was willing to resign on the express condition of receiving an annual allowance of 5,000 livres. On 2nd November 1783, (Festival of the Dead), before an impressive assembly, de Galard “...is put in physical, real and actual possession of the said abbey and all its rights, belongings and dependencies…. “. The Galard banner: “Or, three crows Sable beaked and membered Gules” flew over the abbey tower. ** But the abbey’s profits were only 3600 livres. Understanding that Saint-Maurin was self-sufficient, the new lord-abbot decided to drastically reduce the monks’ share of the community’s assets (the mense), to transfer the costs of justice entirely to the consuls, to raise tithes and to lease certain communal assets of the jurisdiction for his sole benefit. As a result, the surrounding area began to resound with the complaints of the monks and the abbot’s vassals.

Such savings** enabled him to acquire a pretty small chateau, Valende, 2.5km from Saint-Maurin (to the left, off the road to Bourg de Visa), for which he left Saldebru. He then asked the community of Saint-Maurin to repair the roads to Bourg de Visa and Brassac. Their refusal was the beginning of a stormy relationship of increasing violence. Everything in the administration of the jurisdiction caused the formation of factions, of many trials – in which the rights of the abbot were essentially recognised – and, at the instigation of a few leaders, of deeds.

In 1788 these internal quarrels appeared to diminish, through sheer weariness. However, fresh disorders soon arrived from outside the region and the spirit of insubordination returned – at the abbot’s expense.

The chateau of Valende

The coming of the Revolution

In 1789, as a representative of the clergy, he took part in the compiling of the register of grievances (‘cahier de doléances’) of the Clergy of the Agenais. ****.

From February 1790, the party opposed to the abbot carried out acts of violence. In March the new law was applied, Joseph de Galard was deprived of his abbacy and his ecclesiastical benefits in exchange for an ecclesiastical pension; he withdrew to Valende where he tried to build a chapel. As an ordinary priest he celebrated a civic festival in Beauville, probably that of the Federation on 14th July 1790***. At first it appears that, as he was no longer an abbot, he was not subject to the constitutional oath. From August 1792 onwards, anticlerical demands became more radical; on the 14th, a new oath called Liberty-Equality (‘Liberté-Egalité’) was imposed; on the 26th, a law was passed requiring clergymen who had not taken the oath – known as non-juring priests (‘non jureurs’ or ‘refractaires’) – to leave the kingdom within 15 days. Galard, who had refused to swear, did not move.

On March 21st 1793 municipal officers arrived, intending to search his residence; he opposed them, armed and determined.

On 30th March a departmental decree, anticipating the law of 23rd August 1793 (Law of Suspects), ordered the arrest of all refractory priests; three days later a large detachment of the national guard arrived at Valende, but Joseph de Galard had gone.

Flight and end

He took refuge in Bordeaux, an unfortunate choice because the proconsul Tallien and the fierce Lacombe exercised a “Nero-like dictatorship”** there. He changed his name and became a commercial employee of Byrn, a merchant. He was denounced and arrested on 19th December 1793 and brought before the revolutionary tribunal. The latter, having doubts about his identity, sent investigators to Saint-Maurin, which sent the citizens Peros and Labeyrie, “two true sans-culottes”, ** to identify him. They refused to recognise the abbot, but a former mistress, or the woman he had perhaps married, recognised him. This act was either to take revenge for his abandonment of her or to avoid going to the scaffold in her turn* (5).

After 59 days incarcerated in the Fort du Ha, on Monday 17th February 1794 (29 pluviôse an II) Jospeph de Galard was brought before the revolutionary tribunal (in fact the military commission of Bordeaux)*** presided over by the odious Lacombe. His plea, written by himself and simply read at the hearing by his unofficial lawyer, Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, is an inglorious denial: “In the case of the citizen Joseph Galard, born by chance into a noble family and orced to enter holy orders, he anticipated the spirit of the Revolution by his conduct and his aspirations and welcomed it with enthusiasm; he deserved not only acquittal but also the praise of the revolutionary authorities. He claimed to be married, with a long-standing relationship, to “la citoyenne Dumoulin” with whom he had a child*** (6)”.

This defence did him no good and would also have condemned his lawyer if the abbot had not magnanimously taken full responsibility for it. He was condemned to death as an aristocrat representing feudal despotism, for refusing to take the civic oath, for insulting and putting up armed resistance to the magistrates of the Republic. The 32nd and last abbot of Saint-Maurin was executed the same day.

A macabre legend

But the memory of Galard haunts the region and is embellished by legends, notably that of a hidden treasure. It is also said that one of those who had recognised him saw the spectre of the abbot rising every evening, carrying his head under his arm, like Saint Maurin, and then lights slowly going from Valende to nearby Moulineaux. And Saldebru “still vibrates with a shiver of superstitious terror at the memory of the departed … You see, Sir,” say the inhabitants, “this house has been cursed since Montgommery, who, guilty of having killed his prince with the complicity of the Medicis, had sought refuge with us.”**

Yves Desportes

English translation by Jacqui Dean

Notes:

(1) It is necessary to mention here Hector, knight of Saint-Michel, chamberlain of Louis XI, captain of the 120 gentlemen of his guard, whom Pierre Gringonneur, inventor of the card game, popularised in the features of the Jack of diamonds. “Since that time, the males of this family have always had Hector as one of their first names”.

(2) Charles-Amaury’s father, Gaillard de Galard, married in 1579 Françoise de Lézir, daughter of Cyprien de Lézir, lord of Lézir and Saldebru and husband of Jeanne de Lustrac, from a family that between 1425 and 1550 had provided three abbots of the abbey of Saint-Maurin.

(3) A fireback in the castle attests to a construction dating back to at least 1307.

(4) Manor near Saldebru at Perville.

(5) D. Christiaens reports, on the other hand, that Elizabeth Dumoulin displayed uncommon courage to save her lover and produced a promise of marriage dated 25th August 1791, written under private seal, probably forged for the occasion.

(6) Elizabeth Dumoulin was a daughter of the royal notary who registered the possession of the abbey in 1783. A judgement reinstated de Galard’s child, Joseph Galard, to the estate of his natural father.

Bibliography:

*Aymé Vaquier – la Revue de l’Agenais 1905- p548

** Ernest Lafont – Le dernier abbé de Saint-Maurin – la Revue de l’Agenais 1923- pp329/355

*** Daniel Christiaens -Au pied de l’échafaud : le plaidoyer de l’abbé Joseph de Galard

**** M. l’abbé Laffont,Curé du Bugat – bulletin de la SAHTG 1905 T1. Pp 65/94